I try not to spend too much time scrolling through online feeds, but like most of us, I suspect, I often find myself doing it more than I would like, especially these days, when the the news seems to propel us from one disaster to the next. Sometimes, however, something a bit more interesting crops up.

In this case, it was courtesy of NHK World, and was a combination of a broadcast TV programme (for the domestic Japanese audience) and a section with a foreign panel, two of whom, Alexander Bennett and Christopher Glenn, know their stuff with regards to Japanese martial arts and armour (Akino Roza, the other panelist, has more general cultural knowledge). At about 30 minutes, the programme is a reasonable length to make it worth watching, and I think there is something in there for the lay person and enthusiast alike. I have been around Japanese martial arts for a good number of years, but I certainly got something out of it.

https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/shows/5001439/?cid=wohk-fb-org_vod_5001439_dps-202502-001

I am putting the link here, but it will only be available till September 2025, which seems like a long way off now, but for anyone reading after that date, I’m going to describe some of the parts I found more interesting below.

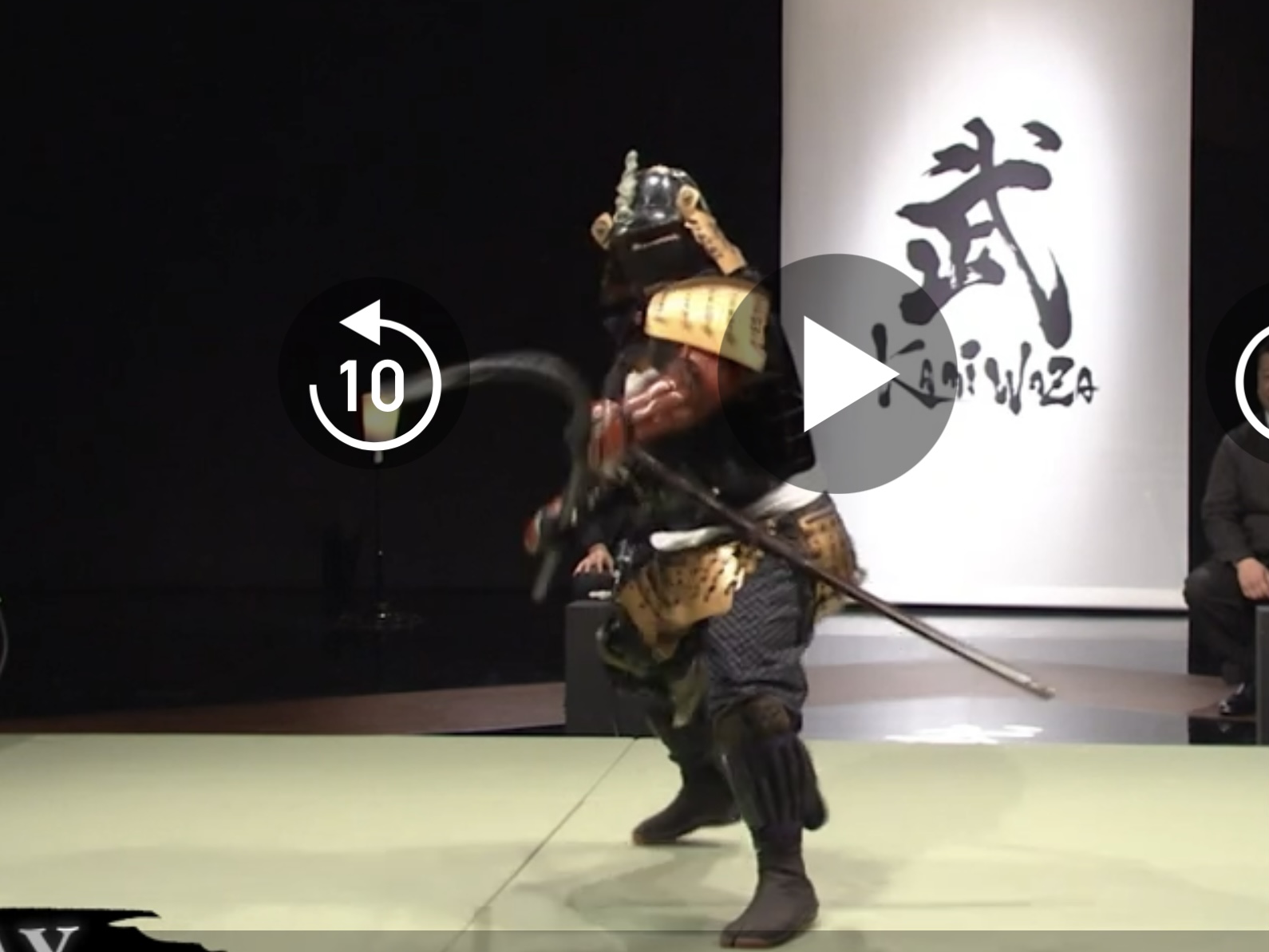

The action begins sometime around the three minute mark, with a demonstration of how spears were used in military formations. Although I have seen some people bitterly protest about the use of spears as, basically, striking weapons which would be raised and then used to strike from above rather than as pointy sticks, the weight of informed opinion seems to be that this was common practice during the Sengoku period (when spears became one of the principal weapons on the battlefield. Indeed, you can well believe that training men to use the spear this way would have been very time efficient.

Anyway, there is a demonstration of the power this technique can produce (yes, we all know boards don’t fight back, but illustrative, all the same). The higher level version of this is also interesting – the use of the flex of the spear shaft is not usually shown in Japanese systems, whereas it is a common feature (sometimes unrealistically so) in Chinese systems, both for usage and also training purposes. I have some experience of Japanese spears, and the shafts certainly do have a certain amount of flexibility – the one used in this demonstration was quite long, and I think that length is certainly an important consideration for this kind of technique. Many Japanese spearheads have a triangular cross-section, which makes them especially suitable for this bludgeoning type of attack. Other types would most likely have been used differently.

Any way, you can see the flex here:

A couple of other points that were interesting were presented in the discussion of foreign the foreign panel. In particular, I found the point about the overlap of armour particularly interesting – the cuirass wrapped around the body with the back overlapping the front on one side. This seems counter-intuitive: a spear thrust might get caught rather than glancing off, for example (although that in itself could be further examined). However, an overlap to the back would also provide a grip for an opponent if they came into grappling range, something you certainly wouldn’t want.

|

| A cuirass showing the overlap coming from behind. |

Moving on, there is also a section on using weapons on horseback, and you get to see the stubby Japanese ponies that were common in those days. There is also a section on Shosho Ryu Yawarajutsu – an early type of jujutsu. This is interesting as preserving aspects that involved fighting an armoured opponent. Many Japanese schools preserve this aspect to a greater or smaller degree – there are several interesting videos online showing techniques from Tenshin Shoden Katori Ryu that many people are probably familiar with – so this may not be new to you, but it is quite interesting all the same.

As well as younger, more mobile members of his dojo, the 87 year old headmaster of the style demonstrates some of the techniques, including kicking someone wearing armour, which is worth seeing.

A well- produced documentary with something for everyone – at least, those who are interested in those kinds of things!