|

| Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795) |

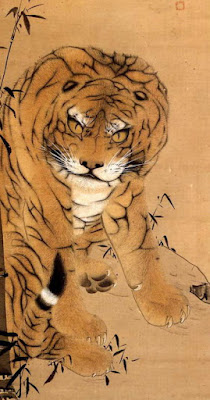

If you were to make a list of typical ‘oriental’ motifs associated with the martial arts, tigers might come somewhere near the top. Not surprisingly, given their strength and ferocity, they have an obvious appeal to those involved in fighting arts. In China, they have provided inspiration for whole systems, as well as components and techniques in many others.

While tigers are native to China, that is not the case with Japan, so there the attitudes and lore concerning these animals is primarily Chinese in origin. In art, as I mentioned in my previous post, early examples of tiger paintings from the continental mainland became models that Japanese artists were to copy for centuries.

|

| Chinese C13th - possibly by Muqi (from the collection of the Tokugawa Museum, Nagoya) |

Traditional Chinese painting (and thus Japanese, too) can be seen as taking a different approach from western art (or at least western art from the renaissance onwards). The cultural concerns of these two streams of art dictated different interests : although both were concerned with depicting reality at a deeper than simply surface level, they differed on what this reality was, their art emphasising themes that had the greatest resonance in each respective culture.

In the west, stylistic developments were connected with increasingly close observation of subjects, combined with an interest in science, particularly optics, but also mathematics, harmonic scales, and anatomy. Developments in these areas can be seen in paintings from the Renaissance onwards. Artists developed an interest in depicting forms ‘in the round’, and utilising their knowledge of perspective, anatomical accuracy, proportion and harmony in composition, as well as the use of camera obscura and other optical aids. Chinese and Japanese artists were also interested in the natural world, but they were less interested in exact physical appearances rather than the spirit of their subjects, including such qualities as strength, softness, and flexibility. This, in turn, required the artist summoning up something of that quality in himself and imparting that during the execution of the work.

|

| Rubens' Tiger Hunt (1616-17). The painter's concern with the accurate physical representation of the tiger is clear. |

Knowing this suggests there may be more to Japanese depictions of tigers than meets the eye. At different periods, different styles are evident, but until relatively modern times, realism was not a primary concern. Certain features are repeated: the glaring eyes; the prominent eyebrows, the rhythmic line of the body, heavy paws, bristling whiskers and sinuous tail, and the stripes that both describe and break up the curves of the body. Rather than depicting a body of flesh and bone, many paintings seem to show a ripple of supple energy in a striped coat.

|

| Kano Sanraku (1559-1635) A contemporary of Rubens, but with different artistic concerns. |

|

| Kano Michinobu (1730-1790) In this later work from the Kano school, the spirit of the tiger seems quite different. |

This may very well be a personal interpretation, and it might be misleading to see Japanese painters as having particular insight into the kinds of energies of interest to bugeisha without any further evidence. Tigers had a range of widely accepted symbolic meanings, some of which were certainly applied to the manners and attitudes of classical bushi. These included the ideas of preparedness (a tiger always sharpens his claws) and virtue (tigers keep their claws sheathed and hide themselves away in bamboo thickets, not outwardly displaying their prowess or threatening others), as well as power and ferocity, and it is highly likely that both the painters and their audience would have had no problem seeing the paintings as illustrative of these. (I discussed an example of this kind of symbolism here).

|

| From Nijo Castle - a sharp-clawed tiger |

There is another area where the symbolism would have been recognisable to members of the warrior class, especially the higher ranking members, and this is the realm of military strategy; in particular, military divination.

Military divination is an area that has seen little research among modern historians, tainted as it is with the whiff of superstition. Nonetheless, it was given serious consideration by those involved in warfare. The link with art comes through research into the work of the 16thcentury monk-painter Sesson Shukei (ca.1492-1577), and has only recently come to light.

Sesson was unusual as a painter; although he was highly accomplished, he did not work in nor had he ever visited the capital, Kyoto, but was based to the east, largely in the Kanto region around Odawara, another burgeoning cultural centre. Sesson travelled a fair bit, not that unusual for monks, from his birthplace in present-day Fukushima down to the Kamakura and Odawara area, and built up connections to several networks of learning, notably his Zen lineage and also the Ashikaga Academy, a center for studying Confucianism, medicine, strategy and I-ching divination, whose graduates often found employment from warlords as advisors, negotiators and diviners, skills that were much in demand in those unsettled times. Not all the roles were military – Confucianism was seen as an important tool of governance and experts who were well versed in these teachings were valuable – but military divination was also one of the valued skill sets.

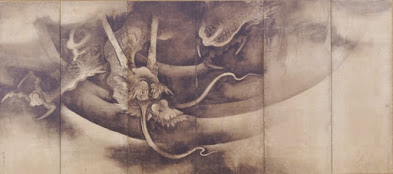

Sesson’s travels took him close to the academy, and several of his works are based on themes closely aligned to its Confucian teachings. It would not have been surprising if he attended lectures there. His mentor and possibly dharma master, Keijo Shisui, had known connections with the academy, while the head of the academy, Kyuka, served Hojo Ujiyasu, the powerful lord of Odawara (and rival of Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin) and it was for Ujiyasu that Sesson painted his screen painting, Dragon and Tiger, (now in the Cleveland Museum of Art. There is another by him or his studio in the Nezu Museum, Tokyo).

All of this is fascinating to me, as I had always felt (or imagined?) these works to embody some kind of deeper understanding related to the mix of spiritual and martial teachings that were connected to the traditional bugei. As yet, there has been little work on this area – Lippit’s own work is very recent – but I look forward to discovering more. I recommend this lecture by Lippit from early 2021 for those who want to know more. (The observations on military divination that I summarised above begin around the 30 minute mark).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=voIECq_k1xE).