|

| A dynamic illustration of Musashi by Noriyoshi Ohrai |

You read enough on a subject, and sooner or later you come to find yourself going round in circles. These days, it seems almost everything you read about Musashi online seems to be rehashing the same information. And don’t get me started on the rash of ‘new translations’ of Gorin no Sho which seem to be blatant copies of the classic translation by Victor Harris (my advice is to check out the “translator” - if almost nothing comes back, you can have a good guess as to where the translation actually comes from).

Occasionally, however, I come across nuggets of information, or stories or opinions that are new to me and seem to carry some weight. Musashi has certainly been a magnet for stories over the years, so much so that it is sometimes difficult to sift out the facts from the fiction. Perhaps, however, it is not always necessary to – the stories have grown up, sometimes in martial traditions, and have become a kind of folklore, the truth of which reflects the opinions and experience of the traditions it comes from. Or to put it another way, they are consistent with what we know about Musashi and might, indeed, be true. Of course, they should have some provenance, too.

So here are a couple items of interest that are unlikely to crop up on a random search online:

First, a (possibly) true story.

At one time, it is said that Musashi was trying to get a position as instructor to the heir apparent to the Shogun. Although the Yagyu school were official instructors to the Tokugawa, (and to a number of other daimyo), that didn’t mean all other schools were shut out (the Itto Ryu headmaster, Ono Tadaaki, was also employed by them). Musashi was beginning to make a name for himself, and somebody thought he was worth checking out.

The story goes that officials from the shogunate came to watch Musashi – they were important people, so I presume this demonstration was put on specially for them. Musashi faced off against his opponent, gradually forcing him back with the strength of his sakki, or killing intention. The officials recognised the uncompromising nature and lethal strength of his spirit and the effectiveness of his technique, but that was not what they wanted for a teacher of a possible heir to the shogun. They were looking for someone with a degree of polish who and who could perhaps play the courtier as occasion demanded. Musashi was all about cutting down the enemy. They told him, “No thank you.”

Although I have found no direct corroboration of this story, it is notable that there were at least a couple of contemporary mentions of Musashi and the Yagyu school together. One commentator who had personal knowledge of both (I forget who, which is very lax, I admit) suggested that even with a handicap, Yagyu Munenori was not a match for Musashi. Also interesting is the copy of Musashi’s Heiho Sanjugokajo (35 articles of Strategy) which was owned and annotated by the Yagyu school. They clearly recognised Musashi’s potential as a rival.

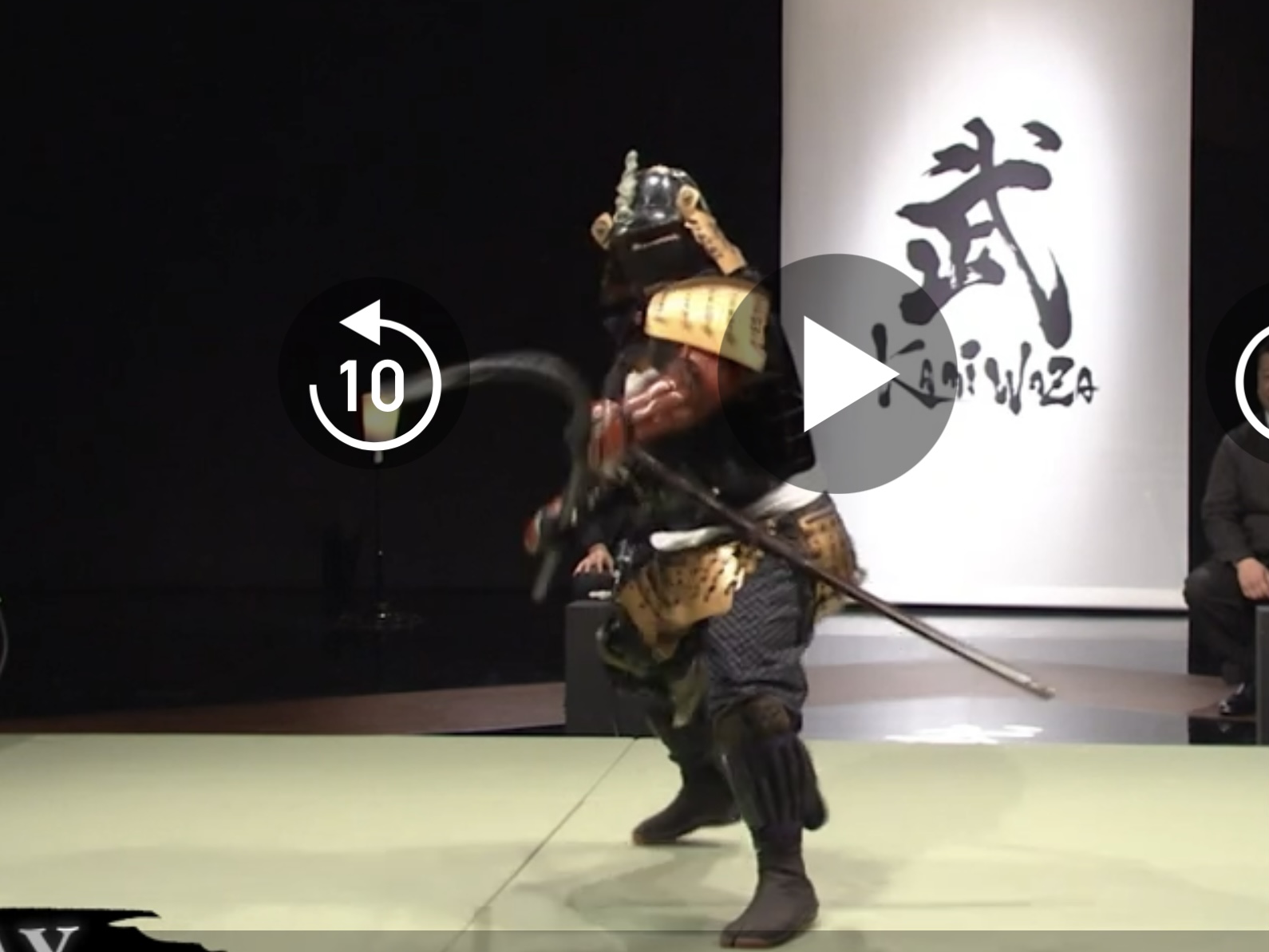

|

| Poster for Duel at Hannyazaka Heights |

Second, a series of articles on the Nakamura Kinnosuke Miyamoto Musashi movies (the same story as the Toshiro Mifune series, which are generally better known in the west).

You can find the site here:

https://www.uchidatomu.com/the-miyamoto-musashi-series-miyamoto-musashi-parts-i-v-1961-1965/2/

Dedicated to the films of Uchida Tomo, this site includes substantial detail on his series of 5 Musashi movies, and a final 6th (with a different studio) that was not really part of the series.

While I appreciate the depth of information and thought that has gone into this, I must say that I disagree with much of the commentary on the films. I acknowledge that David Baldwin (the site owner) writes as an experienced film critic (and connoisseur of Japanese films), but I feel he doesn’t really get the character of Musashi or fully appreciate the milieu in which the films are set. Perhaps, it is that he can’t suspend his disbelief and enter into a story where the major motivating factor is not love, money or revenge, but the desire for self-development. Rather than the sociopath Baldwin characterizes him as, Nakamura Kinnosuke’s Musashi his a man honing his character through his (martial) art. The episodes in the films are illustrations of various aspects of his learning process and illustrate (to a martial artist) some quite interesting points. This is particularly so in the second film in the series (Duel at Hannyazaka Heights) which Baldwin characterizes as the least interesting.

|

| The climactic scene from Duel at Hannyazaka Heights |

To take one example where we differ in opinion, Baldwin complains that Musashi treats Jotaro roughly, pushing him to the ground, and this is an example of his lack of compassion. The scene takes place as Musashi is leaving Nara and has just sighted a group of ne’er do well ronin who have been a source of trouble in the city (and are clearly about to ambush him), as well as a contingent of spear wielding monks from the Hozo-in temple who are seemingly out for revenge. Jotaro starts bawling, begging Musashi to escape. Musashi replies, saying firmly, ‘Samurai are precisely those who don’t run away’, (remember that Jotaro is tagging along with Musashi because he wants to be taught swordsmanship by him). Jotaro continues bawling and Musashi comforts him. Jotaro continues insisting that Musashi escape, Musashi, aware of the fact that he will be fighting for his life in a few moments says, in effect, ‘Ok, get out of here, then’, pushing him away before turning his back and marching to his potential death. Hmm… cruelty? You be the judge.

You can see the scene (or most of it) at about 5:18 in this trailer for the films.

https://natalie.mu/eiga/gallery/news/472699/media/75490

In fact, dealing with fear, (and, indeed, the desire to deal with it as well as other weaknesses) is a fundamental part of the swordsman’s mindset. There is much in Musashi’s approach that reflects the kinds of attitudes that have been promulgated in traditional martial arts for hundreds of years, and certainly, that was the case in my own studies. I came upon a relevant quotation from a Hozo-in densho that includes the line: “the correct attitude (of a student of this school) is always maintaining a high level of dignity”. Kinnosuke does this very successfully.

Still, it’s a good site if you are interested in knowing more about these films (and Uchida Tomo’s work in general) – I first saw them at a festival of samurai movies at the Barbican Centre in London more than 35 years ago – I must admit, I was so bored watching the first one that I almost didn’t come back for the others. I’m glad I did!